When organizing a Commonwealth Reading Series event this past February 2009, I was sorry to learn Cam Terwilliger, a 2008 Fellow in Fiction/Creative Nonfiction, would be unable to participate. But I had to admit, he had a terrific excuse: he’d be in a different hemisphere that month.

I’ll let Cam explain where he was and what he was up to, as he’s graciously agreed to share his Massachusetts-artist-abroad story as an ArtSake guest blogger.

The Nomad Life by Cam Terwilliger

I recently spent a little over five months traveling through parts of Asia in search of I don’t know what. Six months ago, I had just finished a book of short stories and wanted to get away from my routines for a while. But, to be honest, the specifics of my travel plans didn’t extend beyond the following two items: a one-way ticket to Japan to visit a friend, and the vague notion I had saved enough money to travel for 4-6 months. When people asked if I planned to write about the trip in my next book, I often replied mysteriously, “Um. Maybe eventually.” In truth, I have no designs on travel writing, and the next book I plan to write is a historical novel set during the French and Indian war. So what on earth was I doing on a trip to Asia?

At the outset, I had many ideas about using this trip to challenge myself, to experience a true sense of freedomno job, no schedule, no telephone. I had the impulse to see what happened when the world lay open for my perusal, to blow up my life and see what remained. In short, I desired to get to know myself better. This did happen in a way. But it wasn’t the triumphal time I imagined.

From the start, I did everything I was supposed to. I inspected temples. I sampled the live octopus tentacles. I sang the karaoke. I gawked at the world’s largest flower. Still, a sense of unease set in. I had imagined so much freedom would empower me, but more often it gave me a sense of lonely purposelessness as I wandered from Japan to Korea to Malaysia to Thailand. In an email to my sister I described the feeling. I felt hollow. Part of this was merely complaining about the number of tourists clogging up the scenerythough I was little differentbut there was more as well. My very wise sister made the following observation in response to my complaints: “I know that everyone’s impetus to travel is to gain an experience in their livesbut that can only be meaningful if they step outside of themselves. You seem so caught in your emotions and how you are feeling that you haven’t been allowing yourself to engage with the places you are visiting.”

She was right. I was making myself the center of this trip. All I talked about was getting to know myself, challenging myself, me, me, me. I was so fixated on this that I wasnt respecting local cultures on their own terms. This realization cemented itself when I enrolled in a meditation retreat run by several monks in order to escape my own head, but found I was only capable of sitting for hours under their attention, obsessing over my time abroad and what I should do once it was over. Maybe most travelers are this way. But it’s startling to be confronted by the notion that you may, in fact, be a narcissist.

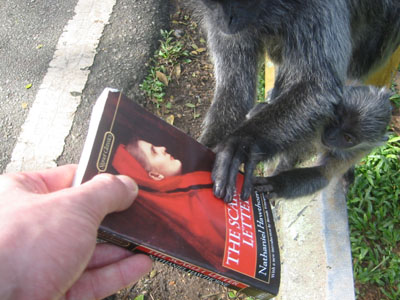

Heading for Laos and Cambodia, I resolved to do my best to focus my energies outward, to engage with the places I visited as my sister suggested. As a writer, I naturally turned to words to do this. It’s true I’d been journaling all along, but now I had a different sense of its importance. Instead of holing up to record my thoughts each day, I decided to use my notebook to observe the world around me, without casting my shadow over it if possible. Specifically, I attempted to describe what I saw in three to four sentences. I thought of these short bits as “word photographs,” and I found the work of thoughtfully observing far more rewarding than snapping off so many easily forgotten pictures with my camera.

To write seriously by hand takes a level of methodical thought that is unique. It makes you ruminate. It makes you wonder: how could I possibly do justice to this person, this scenery, this music? Often, you don’t. But the attempt is satisfying, and it honors what you see with its earnestness. In time, my notebook became so important to me that I imagined it as some vital organ that I carried outside of my body. It had become my gateway into the world, rather than the symbol of self-centered banality it had been.

The notion that the trip would make me into a larger, more complicated, wiser person quickly faded to make room for me to see, really see the world. In fact, as I traveled, the world even seemed to step in to lay me low anytime I got too concerned with myself. When I decided to kayak to an island despite the advice of locals, I was nearly swept out to sea, rescued only at the last moment by a Thai boatman. When I began to mentally congratulate myself for being such a good motorbike driver on a particularly difficult road, I wrecked, and relied on other travelers to bandage me. Weeks passed, and with each one I became less attached to the idea that life owed me something for taking this trip. The feeling culminated upon visiting the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek, a site in Cambodia where hundreds of victims of the Khmer Rouge were buried after being tortured and murdered. At its center stands a monument: a glass tower filled with skulls exhumed from the mass graves that pockmark the land around it like sores. It is impossible not to imagine the good fortune of your own skull when standing before it. It’s impossible not to imagine what these skulls would give to trade places with you. It’s impossible not to grow humble.

Now, I’m home in the US. It’s strange how quickly you can return to the routines of your life. Still, my time away has given me two things I hope will be helpful to my writing, and in my life. The first is humility. This was a long, slow, difficult lesson. However, the second is a pleasant surprise: a new perspective on American people, history, and landscapes. Being around foreign things so long, attempting to see them objectively, can provide you with a fresh set of eyes when looking at your own culture. It’s as though you are seeing it for the first time as well, and you begin to notice details you might otherwise take for granted. And so, in the end, I feel I’m finally ready to write my next bookand humbly grateful for my chance to do so.

Cam Terwilliger’s stories and poems have appeared in The Greensboro Review, The Mid-American Review, The Sycamore Review, 5 AM and elsewhere. In addition to his MCC distinction, Cam has received a Somerville Arts Council Artist Fellowship, has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and in 2004 received an Academy of American Poets Prize.

Jonathan Blask says

Interesting read!